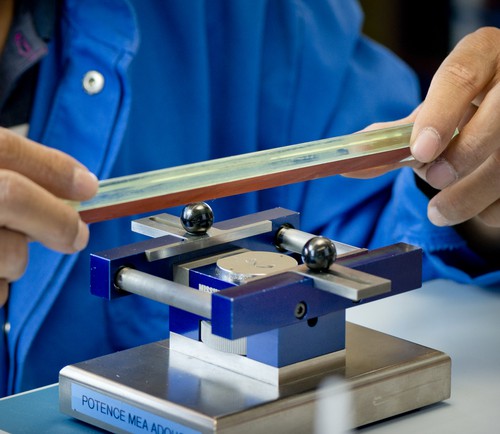

4 - Movement components

Exemplary finishing of movements at Patek Philippe is paramount – for the sake of perfect function as well as aesthetics.

The detailed manual work carried out on the internal components of a watch is where hand-finishing reaches a rare pinnacle. The Patek Philippe Seal requires that movements, as with the rest of the watch, are made using advanced technologies, artisanal know-how, authenticity, and exemplary finishing.

After machining, every movement component – many of which will never be seen – passes through or is finished by human hands, and often decorated. The same processes are applied for all our calibers from Grand Complications to classic calibers. Specific surfaces can be so minuscule that they’re barely perceptible to the naked eye, and craftsmen work with binocular microscopes. This scrupulous fine-tuning is carried out by consummate craftsmen whose raison d’être is the integrity and precision of what they do, and whose fulfillment comes from the fact that everything inside your watch has been honed by them to move with hushed prowess. The quality of finish determines not just how well the part will perform its function, but for how long.

The detailed manual work carried out on the internal components of a watch is where hand-finishing reaches a rare pinnacle. The Patek Philippe Seal requires that movements, as with the rest of the watch, are made using advanced technologies, artisanal know-how, authenticity, and exemplary finishing.

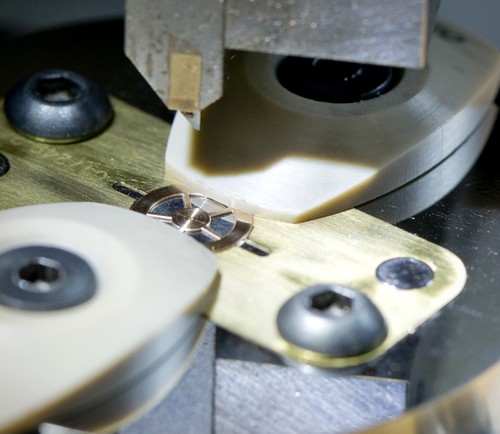

In French, known as anglage. Here, the sharp edge between the surface and the flank is cut away to a smooth 45° curve, then polished to a gleam. One of the most complicated of finish methods, chamfering is time consuming and calls for consummate artisanship. The angle’s surface must be regular and smooth, with parallel edges and a constant width. Use too much pressure and the component deforms; not enough, and the angle won’t be clear and sharp. A chamfer highlights the shape of the part, like a cloud’s silver lining, and when chamfered components are assembled, the play of light is breathtaking. The process also removes any residual burrs.

Using a magnifying eyeglass and a scraper with a slim spear-like head, any minute burrs or remaining scraps of material left by machining on the movement main plate and bridges are removed. The result is not just sleek edges, but enhanced performance, since tiny burrs may, in time, come loose and fall into the watch’s sensitive workings, such as the finely intermeshing wheel-trains.

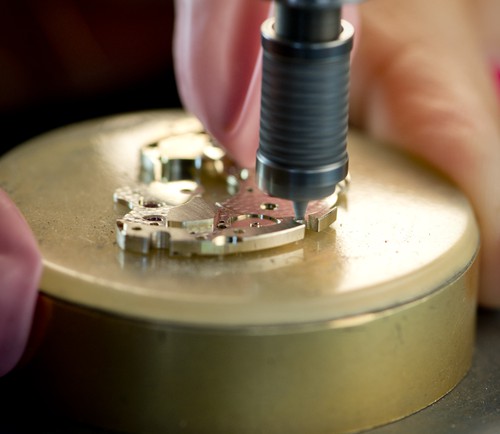

In the past when oils were less stable, the sinking of wheels kept the oil more directed toward the axis. Today, it’s a solely aesthetic job, which goes hand in hand with attention to detail and contributes to the overall refinement of a superb watch. The different wheels (flat metal circles) all receive a polished sink – which is a concave chamfer or slightly hollowed groove. It’s done using a diamond-cutting tool on a mechanical lathe, which is lowered onto the carefully placed piece, where it cuts a circle like a bull’s-eye or Spitfire logo. The sinks – shining, perfect circles – are made one by one.

The last of the 65 steps required by Patek Philippe to finish one pinion – the tiny cogwheels that help drive the gear-train – are composed of an axle and wings – elongated gear teeth known as “leaves.” It’s almost impossible to perform any kind of operation on the very ends of the pinion (the pivots), because they’re so small, but it can be done if the pinion is fitted into a supporting wheel plate with only the pivots protruding. The polish is done with a leather grinding wheel until the operator, checking through magnifying glasses, is satisfied that the ends are smooth and convex.

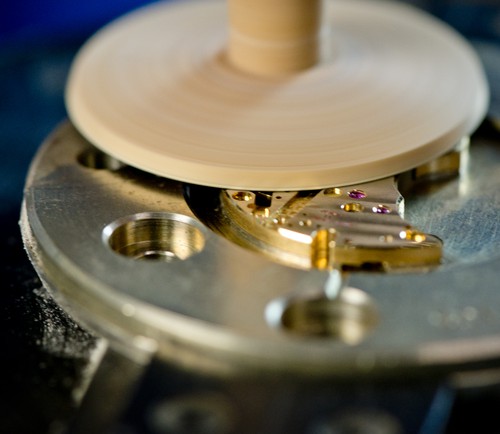

Another operation used on the steel pinion (as well as on some steel wheels), this one aimed at reducing to a minimum any friction or wear and tear on the gears, so guaranteeing the long life and health of the gear-train. Again, the tiny size of the pinion makes this task phenomenally tricky. First, the operator fits the minuscule pinion into a support, paints a thin blue abrasive paste onto it and checks it’s turning freely. Next, the specialist applies another abrasive paste to the wooden grinding wheel, and finally lowers the wooden disk into the cogwheel teeth, which drives the pinion as would happen inside the watch – and at the same time gives the teeth a beautiful smooth and silvery polish.

This poetic term has its basis in solid practicality, cleaning the flat inner planes of the pinion’s teeth (the “leaves”). A hard metal grinding wheel coated with abrasive paste is used for this operation. The steel surface to be polished is so compact that the pinion needs to be supported by being driven into a temporary wheel top (a finished one may be damaged by the machine tools). The result is a gleaming sheen, and surfaces with extra protection against oxidation.

The rippling Côtes de Genève are the most famed of watch decorations, a series of arc-grained bars etched lightly onto a metal surface, for example a movement main plate, bridge, or rotor. At Patek, the procedure is very personal to the artisan, who begins by cutting his own wooden tool. Attached to a grinding wheel, the tool is coated with abrasive and repeatedly pressed down on the component, barely touching it, removing a tiny quantity of material and creating a serene wave pattern. A steady hand is crucial for perfectly straight lines or circular patterns for the rotor.

Also called a black polish, or poli noir, a name it gets from the black or gray shine (depending on the angle at which it’s seen) the finished component radiates. This is a stunning finish and, in high horology, is often found on a wing-shaped tourbillon bridge or a repeater hammer. To achieve that luminous sheen, only possible on steel, the part is gently rubbed in a circular motion on a zinc plate coated with diamond paste, beginning with a coarser grain paste and moving to a fine one. The highest level of polish achievable, it leaves no visible markings on the surface, even under high magnification. The final surface reflects only in one direction, so will appear either to absorb all light and be bottomless ebony, or give off a lucent glow.

In French, called perlage due to the finished resemblance to a row of little pearls. Surfaces of the main plate and the bridges are circular-grained to create a pattern of interlaced circles or bead shapes, arranged like tiles overlapping on a roof. The job is done using a round abrasive polisher fitted into a rotating head; this, the specialist presses down freehand to create the pattern, which must be perfectly linear on each row. The specialist needs a steady hand, rhythm, and a trained eye, and each has his or her own style. Never the same, these decorations, which can feature hundreds of graduated “pearls,” make the part unique. Part of the circular grain pattern can be seen through the sapphire crystal caseback.