3 - Dials

The final touches in the process of making a dial at Patek Philippe involve a series of specialist techniques and crafts that balance beauty with legibility.

If a case is the body that houses a complex structure, then the dial is the very face of a watch, into which we gaze. It’s also what allows the hundreds of components inside a watch to make sense. The dial is a wafer of metal that interprets for us that tiny world of wheels, levers, pinions, and springs beneath it, separating them from the hands and glass.

Making a dial is less a branch of watchmaking, more a dedicated craft in itself. Since the dial is the part of the watch that speaks to us, it must be not only beautiful and harmonious, but clearly legible. Dial makers and finishers use age-old hand-craftsmanship skills, alongside trade secrets passed down through generations. A dial for Patek Philippe takes four to six months of production process work, and from 50 to 200 operations, including decorative techniques.

Each model of dial is different, and for each there is a systematic task list, or “routing”, a bit like a recipe, drawn up so that no one can overlook any of the processes involved – there are over 600 possible task lists, so the right one must be followed for each specific dial! Here’s just one example of a list, for the dial of the grand complication retrograde perpetual calendar Ref. 5159G, with its hand-guilloched center:

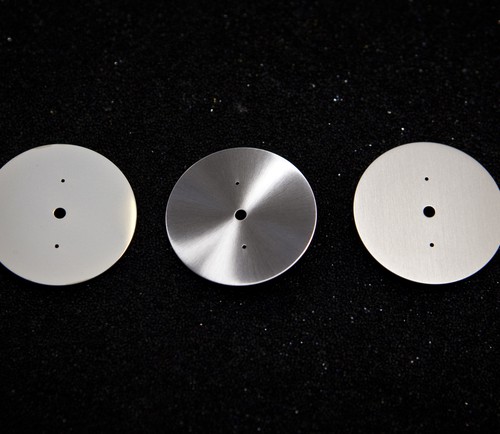

- Blanking the dial plate: outer shape, central hole, stamping apertures

- Soldering the feet to position the dial for subsequent procedures

- Smoothing down: using abrasive paper to remove traces of machining, smooth the surface, and prepare it for polishing

- Polishing or buffing using brushes made from cotton disks, to prepare a perfectly smooth surface ready for the subsequent operations

- Milling (or grinding) a central recess to prepare for guilloché work

- Guillochage: engraving the sunburst pattern grooves

- Electroplating and decoration: during electroplating one metal is electrochemically coated with another to protect against corrosion (for example, plates are protected by a fine layer of rhodium). The dial is then sand-blasted and velvet finished and is given its final color

- Cellulose varnishing: applying a transparent protective varnish

- Manual transfer printing of the words “Patek Philippe Genève” onto the cartouche, adding the “Swiss Made” legend, the numerals, and the chapter ring, the outer band that carries the numerals and symbols

After every single operation, the dial is cleaned in an ultrasound bath with biodegradable detergent.

Enameling, often used by Patek Philippe to decorate cases and dials, is one of the most high-risk of the rare handcrafts. The precarious fusing of powdered glass at ultra-high temperatures can produce heartbreaking disasters but, when successful, the result is luminous beauty, from designs in radiant, jewel-bright colors that will never dull, to lustrous, gently traditional looks.

Over time, this delicate skill has become an endangered one – but not at Patek Philippe, where it has been preserved and nurtured and is used to create breathtakingly lovely pieces (taking anything from several hours to several weeks – or even several months for miniature painting).

The technique involves grinding colored glass or enamel pigments to a talc-like powder, mixing it with water or oil (Patek Philippe usually uses lavender oil), and painting the resulting paste meticulously (sometimes using a brush as fine as a single hair) onto a prepared metal surface. Once dry, the paste is fired in a kiln at temperatures of around 850°C, so that the powdered glass or pigment melts to form a new, impregnable surface and fuses to the metal base.

Dozens of firings may be needed as multiple layers are built up; a coat or two of transparent enamel adds a final depth and brilliance. Because colors can alter during firing, the enamelist must be not just an artist but an alchemist and visionary, able to calculate how the pigments will interact and accurately imagine the finished hues in advance.

The enameler uses one or a combination of age-old techniques – cloisonné, champlevé, paillonné, and miniature painting. For more on each of these complex procedures, see our Rare Handcrafts section.

The Calatrava Ref. 5116, with its calm, plain enamel face. A limited production watch, the pure white parchment of the hand-fired, true enamel dial has a matchless clarity and the luminosity of vellum. Against it, the black Roman numerals of this particular model are stately and robust.

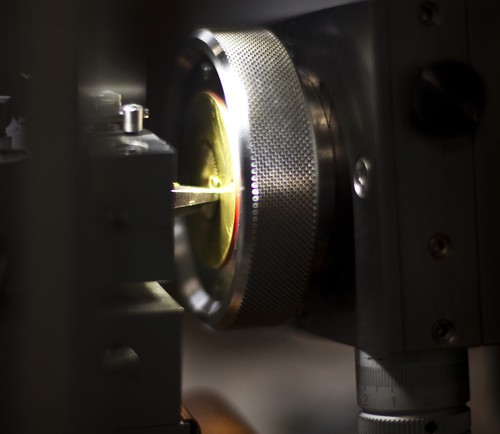

This age-old hand-guilloché technique is used to engrave straight or circular grooves only a few tenths of a millimeter thick, and three to four hundredths of a millimeter deep. The intersecting grooves of guilloché form a patina of endlessly varied motifs to catch and reflect the light; here, they strike out from the center in rays.

There are two main types of lathe: the straight line engine and the rose engine. The first is used to cut straight lines that may intersect at any angle: for example, at 90° for the “hobnail” or Clous de Paris pattern – among the most famous, found on the bezels of Calatrava watches. More widely known and used, the rose engine’s spindle offers a richer variety of motifs, as it can produce curved lines.

The artisan takes pride in knowing his machine by heart as the instructions for use were last seen two centuries ago. Indeed, at Patek Philippe, the rose engines in use are exact copies of those found at the Patek Philippe Museum in Geneva.

Guillochage thrived in watchmaking in the 19th century, but toward the end of the 20th century, it was at risk of becoming extinct along with the artisans who knew how to use the ancient machines. However, as the end of the millennium drew closer and demand surged for fine decorations and geometric patterns, the technique found favor once again and the remaining artisans managed to pass on their knowledge.

Today, true hand-guilloché artisans are few, and they carry out their art thanks to their love of the tradition, kept alive by Patek Philippe.

These operations, many of which are carried out by hand, impart the pigmentation or grain of the dial (matt, half-matt, and so on), and will influence the brilliance and depth of its final color. The craftsman uses an abrasive made from natural rock crushed to a powder as fine as flour, then mixed with water. The regularity of the technique and the consistent blend of the mixture are vital.

- Sunburst: a brush with metal bristles is used with the abrasive paste to create rays spreading from the center to the edges of the dial. This requires an infinitely steady hand. When the completed dial pivots on its axis, it will reveal a glorious sunburst effect

- Vertical satin-brushed: again, a metal-bristle brush and abrasive paste are used. It’s imperative that every bristle of the brush is exactly the same length and completely straight as the brush is drawn downward with exquisite care

- Sand-blasting: the dial is carefully positioned in a machine and ferociously blasted with the crushed rock and water mix until the dial is stippled with a finely grained surface

- Velvet finishing: achieved with two consecutive styles of sand-blasting, first the straightforward original, as above, for a matt surface, and then using cream of tartar as an abrasive, which delivers a cream-colored, downy nap

At this stage, the dials are returned to the electroplating workshop for their final coloring, since galvanization can also be used to impart a rainbow of hues. Getting the perfect color is a multistep procedure involving repeated immersions in chemical baths of different metallic shades to arrive at the right result. For some models, the velvet-finish effect is their final stage; for colored dials, the artwork of the plate is complete when they finally emerge from their second electroplating, resplendent with their subtle new hue.

Dials can also be varnished with a color, anything from black, blue, and lilac to white – you can see this on the steel Aquanaut Luce model, with its variety of dial color options. Otherwise a clear, protective cellulose varnish is applied to the dial once it’s been colored to guard against oxidation.

Varnishing must be carried out in very strictly controlled conditions, in a dedicated cubicle. Tiny particles of dust or even pollution can stick to a dial when varnish is being applied; if this happened, the dial would have to be discarded, however much work had been done on it. For this reason, standards of cleanliness are intense. Clothed in antistatic gear, the operator begins by cleaning the varnishing cubicle with moist wipes. Varnish is applied smoothly, the dials are left to dry naturally in the cubicle, then they’re varnished again to achieve the perfect color.

Rubies, emeralds, sapphires, diamonds – all gems must comply to the Patek Philippe Seal’s strict criteria and be the very best of their kind. In terms of diamonds, only the top D to G color range is acceptable. Diamonds must be of the internally flawless (IF) grade and cut must correspond to the international grades “excellent” to “very good.” Patek Philippe gems are always set by hand, and never bonded with adhesive. Rows of gems must be level and pointing in the same direction. The setter always considers the shape and particular character of each gem in order to bring out its radiant beauty, however gems are to be set, whether in a traditional pattern, randomly (simulating, perhaps, a starry sky) or as baguettes standing as numerals.

Once dials are painted and/or varnished they proceed to décalque, also called tampography or transfer printing. This is the name given to the delicate lithographic process during which any printing to appear on the dial is transferred from the ink on an engraved plate using a silicone pad, and it’s where all the dial inscriptions such as numerals, the chapter ring, counters, and any markings are put in place. A sensitive enough job that it must be done in a “white room” where, again, dust particles or pollution are stringently controlled, and the operator wears overalls and a mask so as not to introduce particles. A steady hand with consistent, even pressure, and a gimlet eye are required. The job may need to be repeated several times with different plates and pads to transfer all the inscriptions – and colors – for a particular dial; in between each layer, the dial is set to dry in an incubator.

Hour indicators may be transfer printed by hand on the dial surface, hand-applied in 18k gold, or created using round or baguette-cut diamonds. The gold and the diamonds are set on appliques, which creates a height to the indicators, slightly increasing contrast. All Patek Philippe hour markers, whatever the dial’s base material, and whether they are index batons, or Roman or Arabic numerals, are 18k gold. As with the dial plate, hour markers go through a lengthy production process before they settle into their final home. There are over a hundred different steps to produce hour markers, but the first stage, as with the dial, will always consist of swaging or blanking (forging the tiny “blanks”).

Next comes facetting. Using a machine fitted with sharply incisive diamond tools, the hour markers are either facetted (cut with small, planed surfaces at the edges, like a gem), flat diamond-polished, or chamfered to make them even more readable. Markers are then all given an individual final polish.

The last operation on the dial is setting the hour marker appliques. This is carried out entirely by hand, and it calls for considerable dexterity and absolute concentration in protecting a dial that has already been the subject of several dozen extremely intricate procedures. Using tweezers, the operator positions the feet of the markers one by one in their appointed place through tiny pilot holes – microscopic perforations into which slot feet so small they are more easily felt with a finger than seen with the eye. Once everything is fitted, the specialist carefully turns the dial over and begins the riveting, fixing the markers definitively by folding their feet flat against the base of the dial, using a hand-held, high-speed diamond grinding wheel or a pointe.

In compliance with the Patek Philippe Seal, applied numerals and/or markers are made of gold and secured in such a way as to guarantee maximum longevity.